On Monday, 9th March 1891, an unexpected and ferocious blizzard descended on the South West of England, leaving an indelible mark on the region’s history. This catastrophic event, now known as the Great Blizzard of 1891, brought life to a standstill across Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, resulting in the tragic loss of over 200 human lives and approximately 6,000 livestock.

The winter preceding the blizzard had been notably harsh, but the weeks leading up to the storm saw a deceptive calm, with milder temperatures and budding flora suggesting an early spring. This tranquillity was shattered on the afternoon of 9th March when temperatures plummeted, and a fine, powdery snow began to fall. By nightfall, the wind had intensified into a full gale from the east, transforming the snowfall into a relentless blizzard.

The blizzard’s impact was immediate and devastating. Snowdrifts reached heights of up to 15 feet, burying homes, roads, and railways. In seaside towns like Dartmouth, Torquay,and Sidmouth, drifts over 11 feet deep were reported. The rural areas and moorlands fared even worse, with entire communities isolated and essential supplies dwindling rapidly.

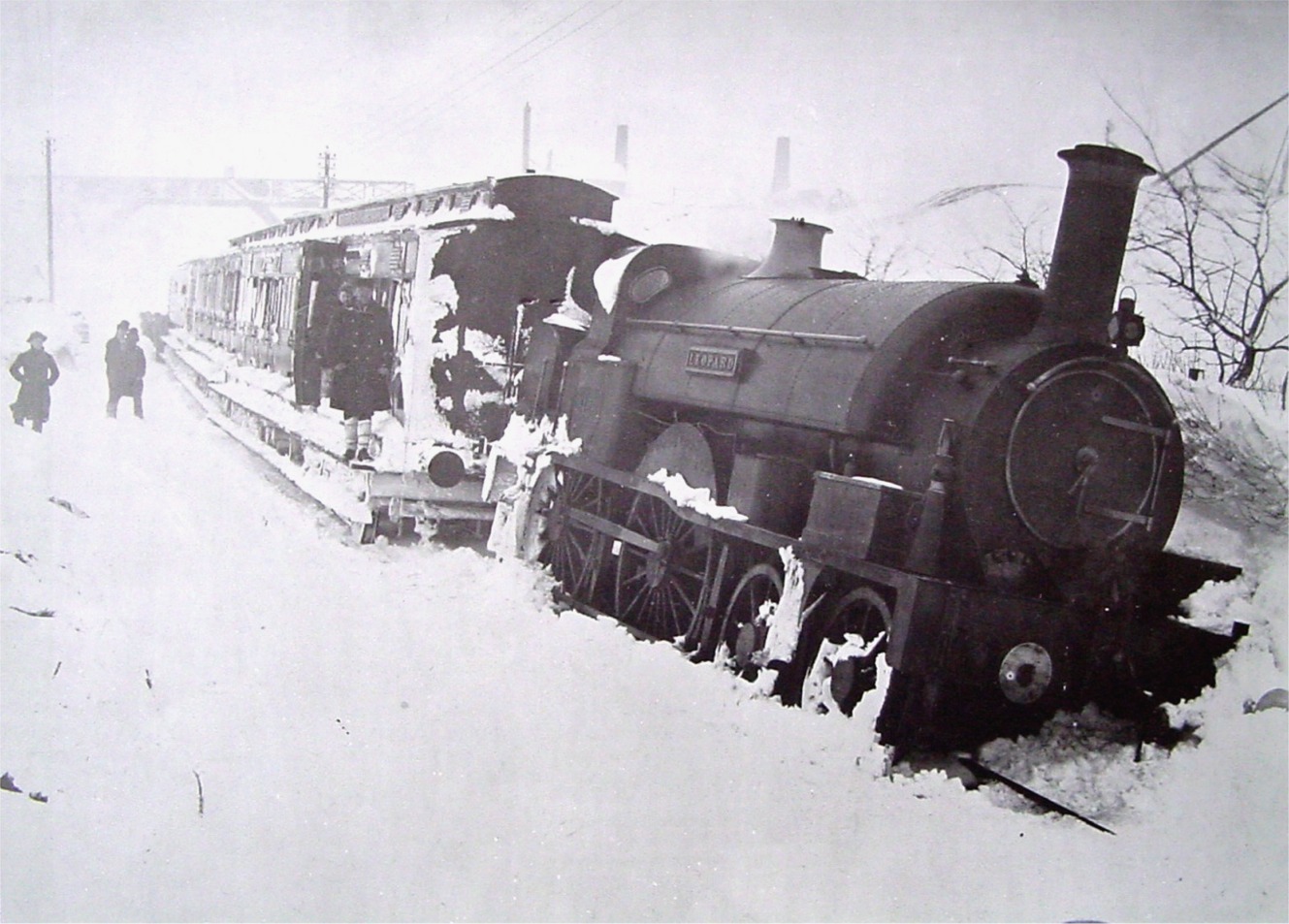

The transportation infrastructure suffered immensely. The Great Western Railway experienced unprecedented disruptions. The mail train to Plymouth was halted by snow at St Germans, forcing eighty passengers to spend the night aboard the stationary train, only resuming their journey after a ten-hour delay. In West Cornwall, three trains were immobilised by the snow, including one near Camborne, where passengers had to trek overland to find shelter. The Helston branch line saw a train embedded in a 15-foot snowdrift, leading to its abandonment.

Maritime activities were equally perilous. The Bay of Panama, a four-masted steel ship en route from Calcutta to Dundee, was driven onto the rocks near the Cornish coast. Eighteen individuals, including the captain’s wife, perished, either drowning or succumbing to the freezing temperatures while clinging to the rigging. This incident was among the most tragic, but it was not isolated; numerous vessels met similar fates along the coast during the storm.

The human toll extended beyond immediate fatalities. Many individuals were trapped in their homes without access to food or heating fuel. The weight of the snow caused roofs to collapse, and telegraph lines were brought down, severing communication. Efforts to clear roads and railways were hampered by the extreme conditions, with some workers tragically freezing to death in their attempts.

The blizzard’s aftermath was a testament to the resilience of the affected communities. Neighbours banded together to dig out homes and share resources. Local farmers faced significant losses, with livestock perishing in the cold, impacting the agricultural economy for years to come. The storm also prompted discussions about improving infrastructure to better withstand such natural disasters in the future.

The Great Blizzard of 1891 was a natural disaster of monumental proportions, highlighting both the vulnerability and the enduring spirit of the communities in South West England. The tales of survival and loss from this period remain a poignant reminder of nature’s unpredictable fury.

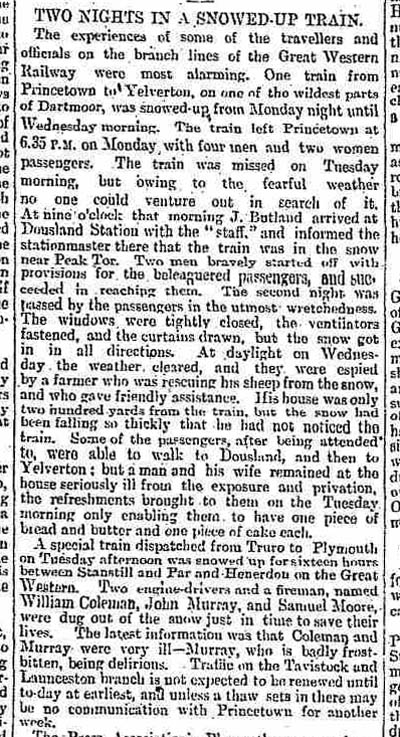

Two Nights In A Snowed Up Train

The Scotsman – Friday 13 March 1891

The experience of some of the travellers and officials on the branch lines of the Great Western Railway were most alarming. One train from Princetown to Yelverton, on one of the wildest parts of Dartmoor, was snowed up from Monday night until Wednesday morning. The train left Princetown at 6.35 PM on Monday with four men and two women passengers. A train was missed on Tuesday morning, but owing to the fearful weather no one could venture out of it.

At 9.00 that morning J. Butland arrived at Dousland Station with the “staff” and informed the station master there that the train was in the snow near Peak Tor. Two men bravely started off with provisions for the beleaguered passengers and succeeded in reaching them.

The second night was passed by the passengers in the most utmost wretchedness. The windows were tightly closed, the ventilators fastened, and the curtains drawn, but the snow got in in all directions. Add daylight on Wednesday the weather cleared and they were espied by a Farmer who was rescuing his sheep from the snow, and who gave friendly assistance. His house was only 200 yards from the train, but the snow had been falling so thickly that he had not notice the train.

Some other passengers, after being attended to, were able to walk to Dousland, and then to Yelverton: that a man and his wife remained at the house seriously ill from exposure and privation, the refreshments brought to them on the Tuesday morning only enabling them to have one piece of bread and butter and one piece of cake each.

A special train despatched from Truro to Plymouth on Tuesday afternoon was snowed up to 16 hours between Standsill and Par and Henderden on the Great Western. two engine drivers and a fireman named William Coleman, John Murray and Samuel Moore, were dug out of the snow just in time to save their lives. The latest information was that Coleman and Murray were very ill – Murray, who is badly frostbitten, being delirious. Traffic on the Tavistock and Launceston branch is not expected to be renewed until today at earliest, and unless a thaw sets in there may be no communication with Princetown for another week.